No nuclear waste in town of Bar Nunn, & Wyoming

DONT TURN THE WYOING JAKEALOPE GREEN

Part Five: The Land Was Spoken For

Jul 27, 2025

They always tell you the nuclear waste plan is new. That this was a recent opportunity. A modern idea. Something Wyoming could debate from scratch.

But it’s not new. In fact, we now know exactly how far back this plan goes.

In the late 1990s, a private company called Nuclear Energy West (NEW Corp.) pitched a national spent nuclear fuel (SNF) storage site in Fremont County—on a very specific parcel near Shoshoni. The proposal was part of the so-called “Owl Creek Energy Project,” and it was serious enough to spark statewide concern and media coverage. It wasn’t theoretical. The land was already picked. It had access to rail, isolation, and private ownership. A perfect target. And that land, we’ve discovered, still exists in the same parcel shape today—under a corporation called 2B Land & Livestock, formed in 1981 by Vincent Picard, a former state senator from Albany County who was born in Shoshoni[^1]. Picard died in 2004, but the land remains in the corporation’s name, with his wife still listed as the registered agent.

The 1990s project faced backlash and was shelved. Or so people thought.

Fast forward to 2025, and suddenly the same kind of plan is back in motion—just dressed in newer clothes. Legislators are floating bills like HB0016 and SF0186 to “study” or “support” SNF storage again. Fremont County is once again the quiet epicenter. And we’re watching the same tactics: obfuscation, insider maneuvering, and no public vote.

And if you think that sounds familiar, it should. A 1998 High Country News report showed that Sen. Bob Peck and then-Rep. Eli Bebout were founding board members of Nuclear Energy West[^2]. That means this entire concept—from site selection to political groundwork—wasn’t an abstract plan. It was a deliberate effort by state insiders who laid the foundation 30 years ago, and who’ve continued to influence uranium and nuclear energy policy ever since.

Now the effort has resurfaced. Same county. Same motives. New front men.

And possibly, the same land.

Sidebar: Why the Tracks Matter

If you’re wondering how spent nuclear fuel (SNF) would even get to Wyoming, here’s the cold, hard truth: you don’t haul highly radioactive waste on a two-lane county road in a cattle trailer.

You haul it by train.

That’s not an opinion—it’s federal policy. SNF is classified as high-level radioactive waste, because it’s exactly that: dangerously radioactive for tens of thousands of years. After it comes out of a reactor, it’s so “hot” it has to cool off in water pools for years before it can even be put into a dry cask. And those casks? They weigh up to 180 tons fully loaded—far too heavy and too hazardous for a semi-truck convoy to drag across Wyoming’s backroads.

That’s why the U.S. Department of Energy, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and the Department of Transportation all agree: rail is the only safe, feasible, and federally approved method for transporting spent fuel across state lines.

Which brings us to Fremont County—and a very specific piece of private land just outside Shoshoni.

Not only is the geology right—dry, remote, and layered with bedrock—but the rail line runs directly through the property.

Yes, you read that right. The same shortline corridor operated by the Bighorn Divide & Wyoming Railroad cuts right across this parcel—the very one tied to the 1990s Nuclear Energy West proposal. A proposal that was shelved, not killed. A plan supported by former legislators who—coincidentally—still have their hands in uranium companies and nuclear legislation today.

You think that’s an accident?

Because if you were quietly trying to build a nuclear waste site in Wyoming, this is exactly what you’d need:

- Private land, to dodge federal siting rules.

- Rail access, to legally transport spent fuel in from out of state.

- Political insulation, built over decades by legacy families and industry insiders.

And now, as legislation inches closer and the public remains distracted, you have to ask:

Was this land always the plan?

Because if the law changes and the paperwork’s already in place, then the train doesn’t need to wait.

It just needs a greenlight.

The UW Study You Weren’t Supposed to See

In early 2025, the University of Wyoming School of Energy Resources quietly published Part Five of its multi-part “Nuclear in Wyoming” series. The final installment focused on spent nuclear fuel and Wyoming’s potential role in long-term SNF storage[^3]. It wasn’t widely shared—at least not with the conservative lawmakers I’ve spoken to. I found it during my own research.

Here’s what it says: the “potential economic benefit” of hosting spent fuel might range from $236 to $612 million over 40 years. But those numbers come with serious strings attached. Wyoming would shoulder the cost of building new infrastructure, security, emergency response systems, monitoring, and long-term maintenance. The “revenue” only materializes if Wyoming does all the heavy lifting and nothing goes wrong.

That’s not an investment. That’s a liability—wrapped in PR.

And conveniently, no one in Cheyenne seemed eager to promote the report.

Speaking with a Forked Tongue

In July, Rep. Lloyd Larsen told Cowboy State Daily that Wyoming is well protected from becoming a nuclear dumping ground because existing laws require state approval for any spent fuel storage[^4].

But let’s be honest: every time Representative Larsen speaks, it’s like he’s buttering up his audience so he can pull a fast one.

Because if we’re already protected, why on earth did Larsen and Sen. Ed Cooper push HB0016 and SF0186 during the last legislative session? Both bills would have set the stage for nuclear waste to come into Wyoming under the guise of a “pilot project” or a “study.” And both would have given agencies broad discretion to move ahead without a vote of the people.

Those bills originated in the Joint Minerals Committee in 2024 and were later presented by Larsen and Cooper to their respective chambers—not necessarily as individual sponsors, but as legislative couriers of a much deeper agenda[^5].

If we’re so protected, why were they trying to change the rules?

Who are they working for?

The $25 Million Loop

Now let’s talk about Radiant Industries.

This California-based startup is promoting an unproven microreactor design it calls “Kaleidos.” The company wants to build a facility in Bar Nunn to manufacture and possibly store its product—but the design hasn’t even been tested. Final validation at Idaho National Lab won’t begin until mid-2026[^6]. In other words, we’re talking about tens of millions of dollars in public funds being committed to a product that doesn’t yet exist.

Enter the Wyoming Business Council’s Business Ready Community (BRC) Grant—a $25 million prize that’s been floated for Radiant.

But Radiant didn’t apply for the grant. The city of Casper supported it. Bar Nunn voted against it. And Advance Casper, a nonprofit “economic development” organization, has been pushing it hard.

If Advance Casper administers the grant, they get to take 5–10% off the top in “management fees,” then control who gets hired to build the site, lay the roads, and supply the materials[^7].

This isn’t economic development. It’s a piggy bank for insiders.

And let’s not forget the risk: Radiant’s plans allow for on-site spent fuel storage if needed. That means Bar Nunn could end up hosting nuclear waste—permanently—without ever voting on it.

Who Pays, Who Profits?

If this all sounds like a raw deal, that’s because it is.

Companies like TerraPower are exempt from Wyoming’s $5-per-megawatt-hour electricity tax because they’re designated as demonstration or training facilities. TerraPower has already received $2 billion in federal support—and they won’t pay taxes on the power they generate[^8].

Radiant may fall into the same bucket. If their customers are federal agencies or other tax-exempt entities, there’s no sales tax collected. So even if they’re selling a product, the state won’t see a dime.

Meanwhile, Wyoming communities shoulder the burden of infrastructure, housing, emergency planning, and future liability.

So again—who really benefits?

This isn’t a conspiracy theory.

It’s a trail of evidence stretching from the 1990s to now. We’ve uncovered the original land parcel. We’ve followed the players from old proposals to current legislative maneuvers. We’ve seen the hidden university study, the grant shell game, the tax exemptions, the insider network, and the resurrection of a nuclear waste plan that never really died.

Is that land near Shoshoni the only possible location? Maybe not. But based on what we’ve seen in the records, what we’ve learned from rail access, and who stands to gain—it still makes the most sense.

And we’ll keep digging.

Because this isn’t just about Radiant, or Fremont County, or any one landowner.

This is about the future of Wyoming—and whether we sell it off, one backroom deal at a time.

One last note: I may be the writer and face of this exposé, but I’m not doing this alone. Behind the scenes, I’m supported by a team of researchers, collaborators, and whistleblowers who care deeply about Wyoming’s future. Many of them work quietly—sending tips, sharing documents, uncovering the threads others would rather keep hidden. So if you’ve made it this far: thank you. And stay tuned.

Footnotes:

[^1]: Wyoming Secretary of State corporate records for 2B Land & Livestock, incorporation date 1981; Vincent Picard obituary (2004); property parcel trace via Fremont County GIS.

[^2]: High Country News, “No Nuclear Jeopardy in Wyoming,” 1998. Link: https://www.hcn.org/issues/130/4163

[^3]: University of Wyoming School of Energy Resources, Nuclear Series Part Five: “Spent Nuclear Fuel,” published February 2025.

[^4]: Cowboy State Daily, “Wyoming Freedom Caucus Opposes Adding More Nuclear Waste Sites,” July 25, 2025.

[^5]: Legislative history for HB0016 and SF0186, 2024 Session. Wyoming Legislature.

[^6]: Radiant Industries INL testing timeline via public presentations; Idaho National Laboratory Dome Building schedule.

[^7]: Wyoming Business Council Business Ready Community Grant Program documents; Advance Casper administrative fee structure.

[^8]: TerraPower exemption under HB0074; Wyoming Department of Revenue interpretations and 2024 public statements.

https://dawnmarquardt.substack.com/p/part-five-the-land-was-spoken-for

Wyoming’s Nuclear Future: The Companies, the Lab, and the Canadian Quiet Giant

Jul 16, 2025

“Nobody’s going to sound the alarm for us. If we want the truth, we have to dig for it ourselves—because the ones making the deals behind the curtain sure aren’t going to tell us. Just look at TerraPower: they passed the tax exemption law in 2020, before the project ever went public. They knew exactly what was coming.”

When I heard Representative Tom Kelly on a recent podcast admit he wasn’t fully up to speed on TerraPower, but had read concerns about the safety of Natrium technology, it got me thinking: What do our legislators actually know about what’s being built in Kemmerer?

While Representative Kelly might not have the details, I’ve been tracking this for months. And here’s a fact that keeps getting buried: TerraPower’s Natrium reactor isn’t just a demonstration plant—it’s tax-exempt, thanks to HB0074, passed in 2020[^1], before the public announcement that Bill Gates was going to plant a stake in Southwestern Wyoming…Think about that for a moment. That bill specifically exempted demonstration small modular nuclear reactors from Wyoming’s electricity tax.

While TerraPower is building a $2 billion federally subsidized reactor[^2], a global training center[^3], and branding Wyoming as the face of advanced nuclear energy, Wyoming taxpayers won’t see a dime in tax revenue from the electricity produced, not while it remains a “demonstration.”

But this is bigger than just one reactor.

Wyoming is being quietly transformed into a national nuclear experiment, not just with reactors, but with an entire nuclear fuel value chain. If you’ve been following headlines, you’ve heard of TerraPower in Kemmerer. Maybe even Radiant Industries, trying to set up a manufacturing plant near Bar Nunn[^4]. And you might have heard of BWXT, the defense contractor looking to supply nuclear fuel for micro-reactors at Wyoming mining sites[^5].

But here’s what most people haven’t heard: Aecon Group, a Canadian infrastructure giant, has been quietly planting flags across Wyoming. Since July 2024, they’ve registered at least six separate corporate entities in the state, covering everything from infrastructure development to industrial services and utilities[^6]. That’s not a guess, that’s a playbook.

Because Wyoming isn’t just being positioned as a place to build reactors, but as a place to mine the uranium, enrich the fuel, fabricate the cores, build the reactors, train the workforce, and eventually store the waste.

If Wyoming wants to be that full-stack nuclear hub, like the Canadians have with their CANDU fleet, they’ll need Aecon’s expertise.

The TerraPower Exception: Tax-Free, Training-Focused

TerraPower is building its Natrium demonstration reactor in Kemmerer, and along with it, a 30,000+ sq. ft. training center to prepare operators for Wyoming’s plant and all future Natrium reactors worldwide[^3].

But thanks to Wyoming’s HB0074 (2020), this demonstration reactor is entirely tax exempt[^1]. That’s right, while the state funds infrastructure and the training center is publicly celebrated, no electricity taxes will be collected on any energy generated from this project while it remains classified as a demonstration.

So TerraPower gets:

- A $2 billion federal subsidy[^2]

- A tax-exempt reactor[^1]

- A global training hub funded and built in Wyoming[^3]

- All while establishing the PR optics that Wyoming is “leading the future of energy”

Meanwhile, the real manufacturing and infrastructure work might just go to outside firms like Bechtel and, silently, Aecon.

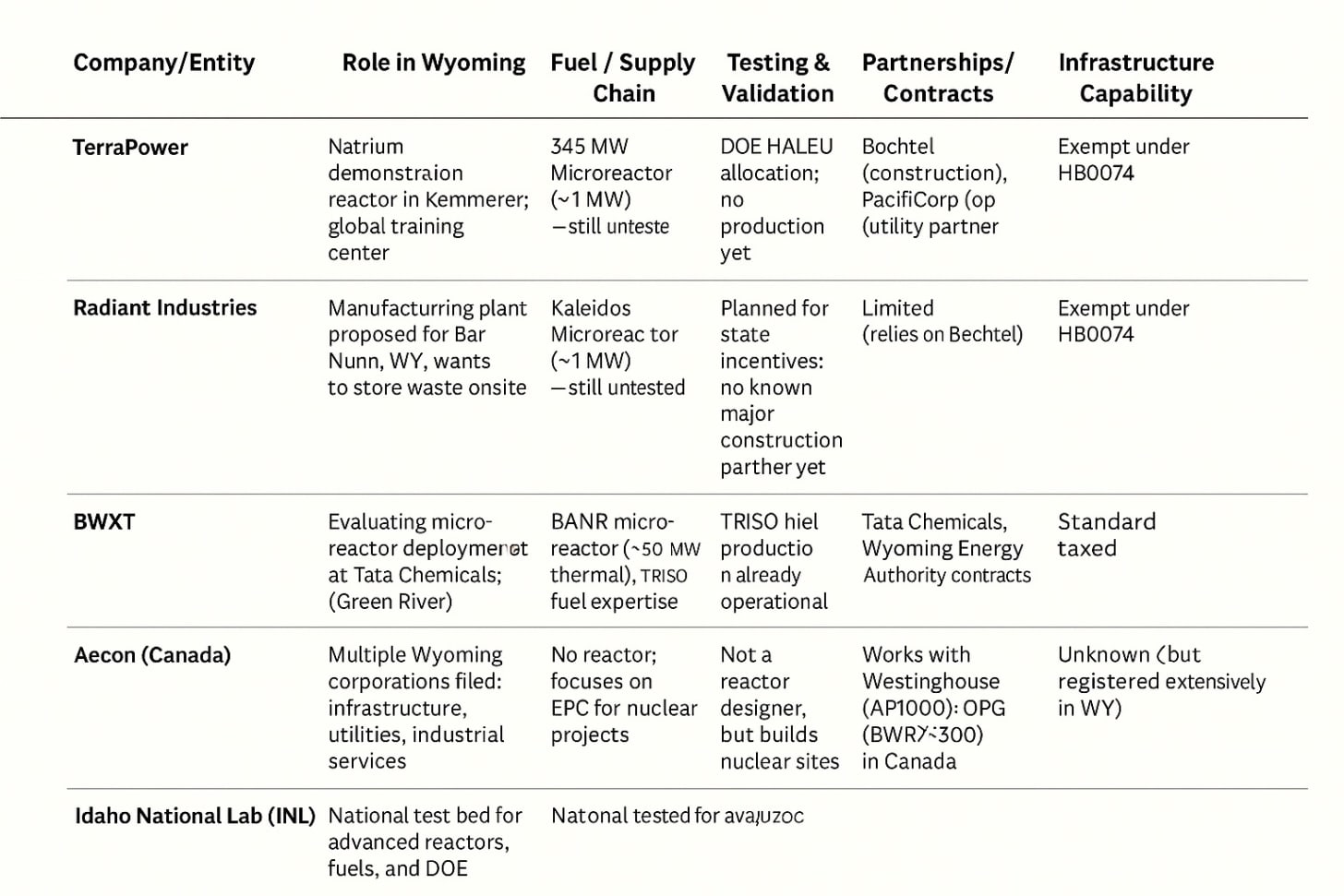

The Players: What They’re Really Doing

- Bechtel gets the high-profile construction contract for the reactor itself[^7].

- Aecon quietly files corporations to be ready for everything else: site prep, utilities, manufacturing facilities, industrial services, and potentially waste management infrastructure[^6].

- Radiant Industries is asking for state and county incentives to build a manufacturing plant for microreactors, despite not having tested a reactor yet[^4].

- BWXT is already producing TRISO nuclear fuel and has a deployment agreement with Tata Chemicals for a microreactor in Green River[^5].

- And INL (Idaho National Lab) remains the essential federal test bed where every private company runs to validate their designs, reactors, and fuels[^8].

Comparative Table: TerraPower, Radiant, BWXT, Aecon, and INL

Sidebar: The Legal Trap Door—How Wyoming Could Get Stuck With Nuclear Waste

In June 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in NRC v. Texas that unless a state or party officially participates in the NRC licensing process, they can’t sue to block a federal license for a nuclear waste storage site[^9]. But the Court didn’t answer whether the NRC even has the legal authority to let private companies store spent nuclear fuel away from reactors, that question remains wide open[^10].

At the same time, Wyoming’s lawmakers have been quietly rewriting the rules:

- SF0186 (2025) would’ve let companies like TerraPower store all of their reactors’ spent fuel in one Wyoming location, even if those reactors are scattered across the state[^11]. The waste would stay here indefinitely under the guise of “temporary dry cask storage.” This bill passed the senate but died in the house.

- HB0016 (2025) tried to strip the Legislature’s power to approve or reject high-level waste storage projects, handing that authority over to the NRC and state regulators without direct legislative say[^12]. Thankfully, it died in committee, but just barely.

Now enter Radiant Industries, pushing to manufacture portable micro-reactors in Wyoming. If the law changes to accommodate them, letting them ship micro-reactors out of state, then return them for refueling or refurbishment, Wyoming could inherit the spent fuel from reactors that never even operated here. If Radiant collapses or sells their site? The waste stays put, and the next buyer could easily convert that “temporary” site into a commercial waste dump for reactors across the country.

In short: change the law for one company, and you’ve opened the legal floodgates. Pair that with the Supreme Court ruling, and Wyoming could soon find itself with no veto power, and a permanent stockpile of nuclear waste it never asked for.

Why This Matters

Wyoming is not just the future home of reactors. It’s being shaped as the nuclear value chain, and yet, most citizens don’t even know who’s involved or what’s at stake.

- Aecon is making a long game play to build everything around these projects[^6].

- TerraPower and Radiant are chasing headlines and federal dollars.

- BWXT is methodically locking down the fuel side of the equation[^5].

- INL remains the gatekeeper for testing and validation—but none of it stays public[^8].

The real question Wyoming citizens should ask:

When these companies cash in, who benefits? Wyoming workers and taxpayers, or just Canadian corporations, Silicon Valley billionaires, and foreign investors?

And remember, Radiant Industries doesn’t even have a tested, proven product yet. Their micro-reactor design still needs to be validated at Idaho National Lab, likely not until 2026 or later[^4]. But that hasn’t stopped them from asking Wyoming taxpayers to invest in their hypothesis, before they’ve proven anything works.

Footnotes

[^1]: Wyoming HB0074, Enrolled Act No. 60, House of Representatives (2020 Budget Session).

[^2]: DOE Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program; TerraPower Natrium award up to $2 billion.

[^3]: TerraPower press release, August 2024 – Kemmerer Training Center announcement.

[^4]: Oil City News, “Natrona County backs $25M grant for Radiant Industries,” June 2025.

[^5]: World Nuclear News, “Tata, BWXT to explore microreactor use at Wyoming site,” July 2024.

[^6]: Wyoming Secretary of State filings; Aecon entities registered July–December 2024.

[^7]: Bechtel press release, partnership with TerraPower for Natrium reactor construction.

[^8]: Idaho National Laboratory, National Reactor Innovation Center support for advanced reactors.

[^9]: Nuclear Regulatory Commission v. Texas, 605 U.S. ___ (2025), Supreme Court decision June 18, 2025.

[^10]: Ibid. Court declined to answer whether NRC has statutory authority for private, away-from-reactor storage.

[^11]: Wyoming Legislature, SF0186 (2025).

[^12]: Wyoming Legislature, HB0016 (2025).